Pitcher Salemburg Born: June 27, 1890 Died: Dec. 12, 1937, Dothan, AL Burial: Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, OH Education: Undetermined Bats: Right Throws: Left Height and Weight: 6-1, 190 Teams and Years: Cincinnati Reds, 1910-15, 1923-25; New York Giants, 1915-21 Awards/Honors: 43, Tar Heel Boys of Summer Top 100

Rube Benton lived life hard. One of his managers found his drinking so worrisome that he included a bonus in his contract if Benton quit. His betting on ballgames sucked him into the sport’s most-notorious scandal, the alleged fixing of the 1919 World Series. He acquired such an unsavory reputation as a result that club owners wanted him banned from the game. His reckless driving, likely influenced by alcohol, led to three serious accidents. The last one killed him.

Despite all that, Benton was one of the Dead Ball Era’s better pitchers. He was a reliable starter atop the New York Giants’ pitching staff and was brilliant in the 1917 World Series, pitching 14 innings without giving up an earned run. He once threw 17 scoreless innings in a game before his Giants scored seven runs to win. Benton pitched in the minor leagues well into his 40s and finished with more than 300 victories as a professional. He ranks 43rd in the Tar Heels Boys of Summer Top 100 players.

Born in 1890 on a farm near Clinton, North Carolina, John Cleave Benton was one of John and Edith’s four children. We know nothing about his childhood or education or why he ended up in Fort Mill, South Carolina, in 1909 playing for a textile team.

A year later, he signed with the Peaches, then a Class C club in Macon, Georgia, and became a sensation. He won 11 games during the first three months of the season while striking out as many as 20 a contest with one of the best curve balls anyone in the South Atlantic League had ever seen. Three big-league clubs bid for Benton at midseason, with the Cincinnati Reds buying his contract for the unusually high price of $3,500, or the equivalent of about $110,000 today. Some sources put the final price tag as high as $7,500, which would have been a record for a Class C player.

Reds’ Manager Clark Griffith noticed something odd when his new expensive, lefthander arrived in Cincinnati a few days later. The kid had a bad habit of rubbing the ball on his hip after getting into a set position on the mound. Big-league umpires, Griffith knew, would be tempted to consider the movement a balk. A pitcher in his playing days, Griffith gave Benton some instruction and told him to be careful before he sent him out for his debut on June 28, 1910, a day after his 20th birthday.

It was a tough initiation. The Chicago Cubs, one of the era’s perennial powerhouses, would win 104 games on the way to their fourth pennant in five years. Their ace and one of the legends of the game, Mordecai Brown, took the mound to face the rookie. The crafty veteran with the mangled pitching hand and the colorful nickname Three Finger threw a bewildering array of pitches that would win him 25 games that season and, eventually, earn him a plaque on the wall in Cooperstown. Brown actually had more fingers than that on his right hand. He lost half of his index finger in a farming accident when he was a child. He later fell while chasing rabbits, breaking what was left. He ended up with a paralyzed pinky, a bent middle finger, and a stump for an index finger. Three Finger, though, could fit in a headline much easier than Four-And-a-Half Finger Brown.

As Giffith had feared, Augie Moran, the home plate umpire, called a balk in the first inning. Benton seemed shaken. In the second, Cubs’ shortstop Joe Tinker – he of the famous trio of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance -- singled and took a long lead off first.1 He finally walked to second while Benton watched. After a single sent him to third, Tinker leisurely meandered home. Benton again did nothing. Christy Mathewson, the erudite Giants’ pitcher and another legend of the era, often wrote newspaper columns about baseball. He reported what happened in the dugout when the inning was blessedly over. Griffith demanded to know why Benton held onto the ball. “Huh?” Rube snorted. “I guess I wasn’t going to let that guy pull anything on me, was I? He didn’t get me to balk, did he?” Benton had acquired the nickname then common for farm boys from the South long before he joined the Reds, but if Mathewson’s quote is accurate – and who would question someone they called The Christian Gentleman? – Rube earned it that day.

It was all downhill from there. Benton lasted just five innings, giving up nine runs while walking seven in an 11-1 drubbing. Ren Mulford, a columnist for Sporting Life magazine, noted that the game proved that the young pitcher needed “polishing.” “Pitching to hayseeds and striking them out in bunches doesn’t qualify for a whole lot,” he wrote. “There’s a wide margin between fan outs on a Georgia plantation and a National League field.” It must have been a “glorious bit of comedy” to watch the Cubs steal bases while Benton held the ball, Mulford continued, but he noted that even the gods started out a bit wide-eyed. “There was a time when Denton (Cy) Young was so green that the cows used to gaze at him in a wistful way, but he got there.”

Benton decided, though, that he needed a vacation first. Maybe it was the stress of it all or a deep longing for home, but he disappeared for a week in August without telling Griffith. A ‘French holiday,” the newspapers called it. The manager contacted someone he knew in Clinton, who went out to look for the wayward pitcher. He found Benton on the family farm in nearby Salemburg. “He says that he had a nice little vacation and enjoyed the feel of the swamps under his hoofs after his experience with the cobblestone pavements of Cincy,” a newspaper reported. Benton was put on a train “in charge of one of the club waiters, otherwise he would have never found his way to the Brooklyn grounds where the Reds were playing.” Griffith docked him eight days’ pay.

Frank’s book, The Tar Heel Boys of Summer: North Carolina’s Major League Ballplayers, will be published later this year. It will feature 34 biographical profiles of the more than 500 state natives who played in major-league baseball. I’ll post here some that didn’t make into the book.

Benton appeared in 11 more games that season without recording a victory and gave up almost five runs an outing. The Reds sent him to the Class A Lookouts in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to start the 1911 season. Benton won 18 games there and returned to Cincinnati at the end of the year. He wouldn’t play in the minors again until he was exiled by the owners a decade later.

After a decent return season when he won 18 and led the league in starts and appearances, 1913 was another disaster likely triggered by Benton’s drinking. He took another French holiday, disappearing for a week in early July. When he returned, Benton sauntered into the clubhouse before a game “with the usual smile on his cheerful countenance.” As the baseball gods would have it, though, Tinker was waiting for him. After retiring as a player, he had taken the Reds’ reins at the start of the season as their new manager, and he wasn’t interested in excuses. He told Benton that he was suspended indefinitely, fined $100 ($3,000), and docked three days’ pay. “If I had known that,” the pitcher responded, “I would not have come back.” Take the first train home, Tinker retorted. Benton dressed into his uniform and threw batting practice. The manager later told reporters that he would lift the suspension when Benton was “in good condition and ready to pitch.” Drinking, gambling, womanizing – all common vices of players of the era – were rarely talked about openly or reported in the press. Readers needed to know the euphemisms to understand what was really going on. Tinker was tipping them off.

Ten days later, Benton was returning at night from a boxing match, where he likely placed a few bets and had a few drinks. Witnesses later reported that he was driving his motorcycle fast and recklessly when he crashed head-on into a streetcar. He was unconscious when he was taken to the hospital, and some initial newspaper stories reported that the accident was fatal. It did fracture his jaw in several places and ended his season. The Reds said they wouldn’t pay his salary or his doctor bills because Tinker had ordered Benton to get rid of the motorcycle after a minor accident a month earlier. Club President Gary Herrmann gave Reds’ fans another hint. ““We cannot afford to pay high salaries to players who do not take care of themselves,” he told the newspapers.

Benton came back in 1914 and had his best season with the Reds, winning 16 games with a 2.96 ERA for a last-place team. He won only six more through August of the following year, however, and the Reds placed him on waivers. The Giants took a chance on him.

Manager John McGraw didn’t like Benton’s drinking, but under his hard eye the pitcher blossomed. Benton won 31 games in his first two full seasons in New York. With his team down 2-0 in the 1917 World Series, he became the first lefty to toss a shutout in the series by beating the Chicago White Sox, 2-0. He lost the final Game 6, despite not giving up an earned run in his five innings of work. After spending a year in the Army in 1918, he had his best season as a major leaguer when he returned, going 17-11 with a 2.63 ERA. “At one time, he was a happy-go-lucky sort of fellow, but since joining the Giants, he has applied himself diligently to his art,” was the way Mathewson described the transformation. Hint, hint.

The gambling then caught up with him. Betting on the outcome of games by players, coaches, and fans was as much a feature of early baseball as the double play. Bookies roamed the grandstands along with the beer vendors, and players were at times offered money to ensure that their teams lost. Benton, who admitted that he bet on games, said he was asked twice to throw games but refused each time. Everyone involved in the sport reluctantly looked the other way, but the issue couldn’t be ignored after the 1919 World Series. Several players of the American League champion White Sox were rumored to have conspired with gamblers to rig the outcome of the sport’s featured contest, which the Reds won.

A grand jury in Chicago spent 1920 investigating the series and baseball gambling in general. Because he had admitted to being approached by gamblers to throw games and boasted to players that he had made $3,800 ($71,000) betting on the series, Benton was among those subpoenaed. He admitted to reporters before testifying that he knew after the series that a “prominent gambling syndicate” had fixed it for $100,000 ($1.8 million). Five White Sox players were involved, he said. “I’m not out to get anybody in bad,” he said, “but I am out to do anything I can to clean up this situation.” He denied making money betting on the series.

Despite a 5-2 record and 2.88 ERA, Benton was released by the Giants in July 1921. The club’s official explanation: “Failure to keep in condition after repeated warnings.” Maybe that was another euphemism for Benton’s drinking, but it could also have been the cover for getting rid of a player who carried the lingering stench of a fixed World Series.

If there was such an odor, the Saints in St. Paul, Minnesota, didn’t mind. They immediately signed Benton, who won a career-high 21 games the following year and led the team to the Class AA American Association pennant.

Pitching winning baseball apparently can be a powerful deodorant because two big-league clubs, the St. Louis Browns and the Reds – wanted to sign Benton. Ban Johnson, the American League president, decreed that Benton couldn’t play in his league because he knew about the World Series fix and didn’t report it. The Browns backed off. National League club owners beseeched Herrmann not to sign his old southpaw. “It is simply felt that he is not the kind of player we want in our ranks,” a league official said. “Certainly, we have the right to pick the kind of player we want in our ranks.” Herrmann ignored his fellow owners and traded for Benton in January 1923. League owners met a month later and voted to let the new guy, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, decide the matter.

Owners in both leagues had hired the former federal judge in 1920 as baseball’s first commissioner and gave him absolute authority to restore confidence in the game. Landis responded the following year by banning eight White Sox players from organized baseball for either fixing the series or knowing about it. All had been acquitted of criminal charges. Baseball historians have debated the merits of the bans ever since, and the record of who may have done what remains murky. Landis’ drastic action, though, had the effect he intended: Open betting on games by players and coaches was never again a major issue,, and bookies were forced out of the grandstands and into the bars across the street. The owners were reliably certain that their man would also bring the hammer down on another player they considered undesirable.

Landis shocked them by ruling a couple of weeks later that Benton could pitch for the Reds. The charges against him should have been leveled and investigated before he was allowed to sign with St. Paul, the commissioner reasoned. His investigation, he said, didn’t uncover anything new or suspicious. An irate John Heydler, president of the National League, declared that Benton would be banned from his league regardless of the commissioner’s ruling, and several club owners said they would protest any game with the Reds that Benton pitched. The player was distraught. “I did think my troubles were over when Judge Landis made his ruling the other day,”Benton said. “I do not understand why they are still hounding me.”

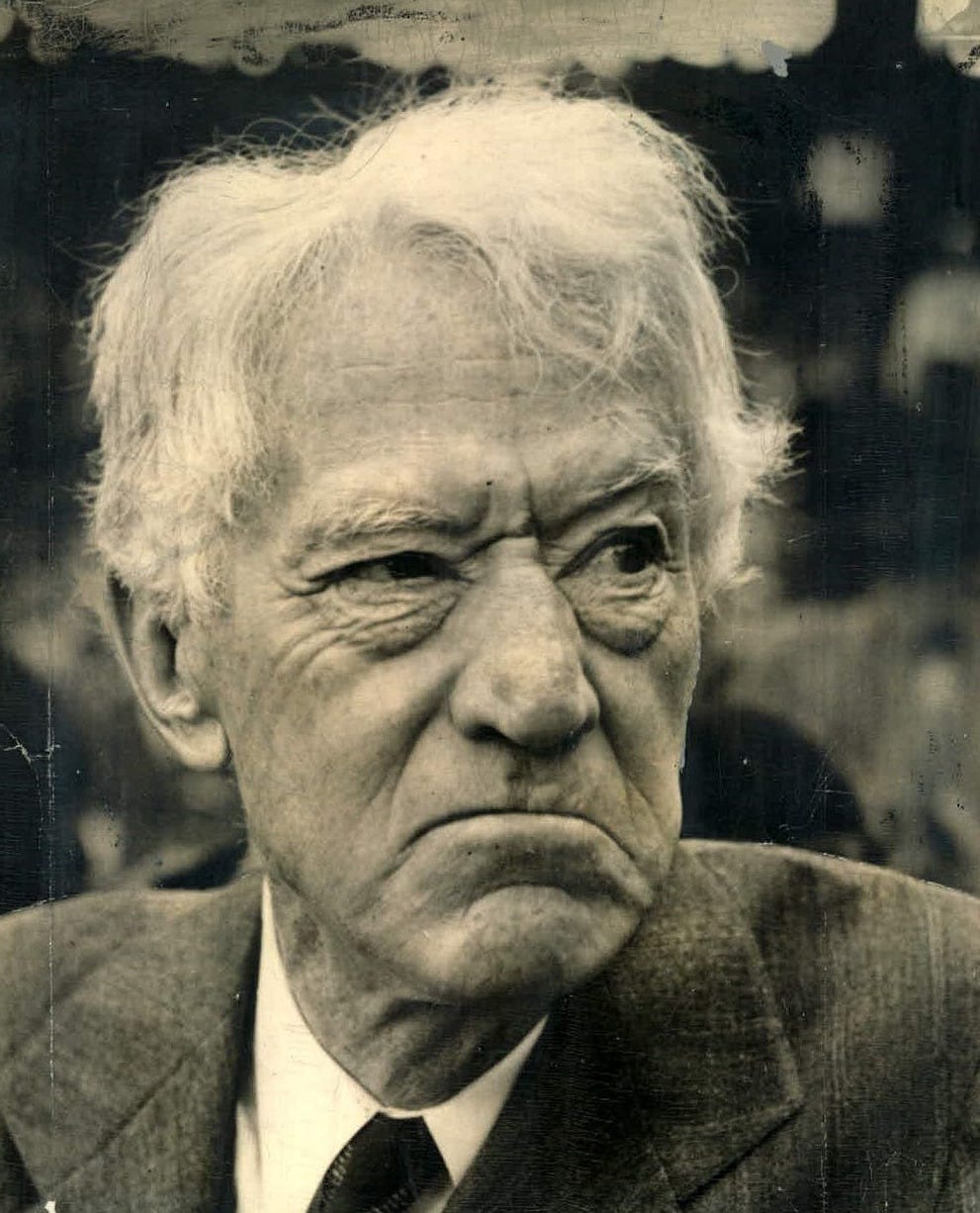

Landis, as many players and owner were learning, wasn’t a man to trifle with. At turns theatrical and taciturn, he had an unruly shock of white hair over a perpetual expression of seriousness that bordered on a scowl. His stiff, starched shirts intimated that the man inside them was just as uncompromising. Landis summoned Heydler to his office in Chicago and likely reminded him that his contract gave him unquestioned authority over everyone in baseball, from the bat boy up to, yes, the owner. He could fine, suspended, or ban anyone for any reason. There was no appeal. A chastened Heydler left and said no more about the matter, and the protests never materialized.

In that dramatic way, Benton returned to the majors and was an effective pitcher for the Reds, winning one more game than he lost, over the next three years. The team released him after the 1925 season.

Within a few months, he was happily reunited with Mike Kelley, his old manager in St. Paul. Kelley had since moved to sister city Minneapolis, where he owned and managed the rival Millers. Benton won 115 games for him over the next eight seasons and, indeed another pennant, but calamity struck first in the form of another screeching motor vehicle.

On the day before Thanksgiving 1931, the car Benton was driving swerved on an icy road near Lawrenceburg, Indiana. According to some reports, he tried to avoid a hay wagon. The car rolled over a couple of times before coming to a stop in front of a cemetery. Benton lay unconscious in a hospital for three days. Doctors said his skull was fractured and his hands crushed. He’d likely survive, they said, but his pitching days were over.

Three days before the Millers were to report to training camp the following spring, Benton called Kelley asking about his contract. “Surely, Rube, a man of your age does not expect to continue in baseball after such an accident?” the owner replied.[Benton would turn 42 during the season. The pitcher insisted that he was fine. “I’ve had operations performed on both of my hands and now have use of my fingers.” He explained. “The hole in my skull has been plugged and my face has been patched. I have paid surgeons $1,200 ($23,000) to get into condition. Please let me prove this to you, Mike. What’s more I have cut out all foolishness since the wreck.” Benton was Kelley’s Opening Day starter. He won 18 games that season and led the Millers to the American Association championship.

Released in 1934, he continued pitching in the low minors until the day his luck finally ran out. Benton died in December 1937 in a head-on collision near Ozark, Arkansas, where he had been hunting. A passenger is his car also died. He left behind his wife of almost 20 years, Elsie, and a daughter.

Cubs’ first baseman Fank Chance and second baseman Johnny Evers joined Tinker in a famous poem published in 1910. Baseball’s Sad Lexicon, written by Giants’ fan Franklin Pierce Adams, is a rueful lament of another rally snuffed out by another Cubs’ double play. The poem’s popularity likely got the three elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“These are the saddest of possible words:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

I’m not a baseball fan defined by skill, statistics and rankings but I love to read these profiles. Frank’s colorful, descriptive language unique to baseball paints a picture of times in which players appear to have lived just to play.