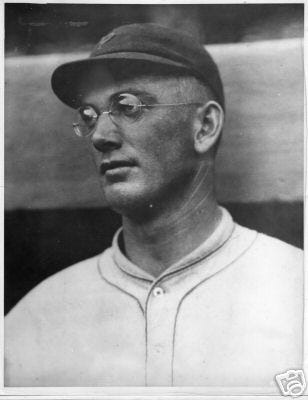

Pitcher Oxford Nickname: Specs Born: July 12, 1894 Died: Jan. 29, 1963, Daytona Beach, FL Education: Horner Military School, Oxford Bats: Left Throws: Right Height and Weight: 6-0, 190 Teams and Years: St. Louis Cardinals, 1915-19; Philadelphia Phillies, 1919-23; Pittsburgh Pirates, 1923-29 Awards/Honors: N.C. Sports Hall of Fame, 1992; 22, Tar Heel Boys of Summer Top 100

As the first player in almost three decades to wear eyeglasses on the field, Lee Meadows was an oddity when he came up in 1915. Most managers wouldn’t take a chance on him, and players and fans taunted him. He was considered so strange that during his 15 years in the majors almost every newspaper story described him as the “spectacled,” “bespectacled,” or even “four-eyed” pitcher.

As Meadows proved, it was silly even then to think that a guy with glasses couldn’t pitch as well as one without them. His spectacles, unfortunately, became the defining feature of his career, obscuring the very good, tenacious pitcher who wore them. Though he played most of his career for some really lousy teams, Meadows ended up in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame as one of the state’s top pitchers. He’s 22 on our Tar Heel Boys of Summer Top 100. A compelling argument could be made that Meadows would have had a shot at the big hall in Cooperstown had a manager of one of the era’s contending teams broken tradition and given the nearsighted rookie with glasses a second look.

Henry Lee Meadows wore those “cheaters,” as some ballplayers called them at the time, since his childhood in Oxford, North Carolina, where he was born in 1894. He was the second of John and Cora Meadows’ four children and their only son. He attended Horner Military School, a private secondary school in Oxford, where he pitched, played football, ran track, and was a good swimmer. He also showed the intelligence that later marked him as a thinking man’s pitcher.1 He was so well-versed in botany, for instance, that he taught the subject his senior year, and he would have been welcomed back as a teacher after he graduated in 1913.

Frank’s book, The Tar Heel Boys of Summer: North Carolina’s Major League Ballplayers, will be published later this year. It will feature 34 biographical profiles of the more than 500 state natives who played in major-league baseball. I’ll post here some that didn’t make into the book.

He, instead, chose to chase his dream. That spring, Meadows joined the Bulls, a Class D club in Durham, North Carolina, and won 40 games over the next two seasons. Most big-league managers, however, considered him little more than a novelty act. John McGraw of the New York Giants said he didn’t want “a blind man” on his pitching staff. Earl Mack, Connie’s son, wouldn’t recommend that his father sign the rookie for the Philadelphia Athletics. “I don’t think Pa would fancy the idea of carrying a pitcher who can’t see,” he said. Meadows wasn’t surprised. As a child, he always feared that his glasses were anchors. “All the time I was afraid there was no chance for even if I proved to have the ability as I grew older the fact that I was obliged to wear glasses seemed to shut me off from any opportunity in the big leagues,” he said.

Luckily, Bob Connery, a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, wasn’t blinded by convention. All he saw was a 40-game winner, and he signed Meadows, who became the first major-leaguer to wear glasses since Will White of Cincinnati in the old American Association in 1886.2 Meadows’ spectacles, of course, drew the attention of sports reporters who never tired of writing about them during spring training in 1915. “We trust the fans of St. Louis will not forget the fact that pitcher Lee Meadows of the Cardinals wears glasses,” St. Louis sports columnist L.C. Davis playfully noted in a not-to-subtle swipe at his fellow scribes. “We mention this as nothing has been said about it for the last two days.”

His glasses firmly in place, Meadows marched out from the bullpen for his debut on April 19. With a fluid sidearm, almost underhanded, motion and relying on a good curve, fastball, and spitball, which was then legal, he threw six shutout innings in relief. By July, he was making believers of the skeptics. After he tossed a one-hitter against the Cincinnati Reds, Ward Mason of Baseball Magazine noted that Meadows “taught the baseball world that a pitcher with weak eyes may yet win renown in the major leagues.” He won 13 games that rookie season with a 2.99 earned run average, or ERA, not a bad showing for a supposedly blind, Class D rookie on a sixth-place team.

That first season, however, was one of the few high spots of Meadows’ four years on a club that resided mostly at the bottom of the National League standings. He lost 23 games, though with a very respectable 2.58 ERA, in his sophomore season when the Cardinals slipped to seventh place.

Fans and opposing players made all that losing more difficult. “When I think of my early training, I have to laugh,” he remembered a decade later. “What they didn’t call me – the usual stuff. ‘That four-eyed guy, that cross-eyed bloke, mamma’s pet. . .. take them off and I’ll sock you right in the nose.’” He credited skipper Miller Huggins, a Hall of Famer after later managing the New York Yankees to six pennants, for getting him through the toughest times. “Back there in 1915, I sat on the bench in front of my locker many times and wondered whether the price I had to pay on the insults was worth it,” Meadows said. “Huggins always encouraged me.”

Though the heckling stopped, the losing got even worse after Meadows was traded to the woeful Philadelphia Phillies during the 1919 season. They were even worse than the Cardinals, finishing last in the National League for two of the three full seasons Meadows was on the team. He was their best pitcher, however, even in 1920 when he fouled a ball off in batting practice and shattered his glasses. Doctors removed shards from his eyes and feared he’d never pitch again. He recovered at home and made a remarkable comeback, winning 16 games for the league’s worst team and earning the respect of opposing managers and the reporters who covered him. “[There] is no quit in this man’s make-up,” a one noted.

By 1923, Meadows made clear he was fed up with pitching for a dead-end club. The press speculated that McGraw, who realized his error and had tried to trade for Meadows several times, would finally land his man. In a surprise move, the Phillies dealt him in May to the Pittsburgh Pirates instead. Finally playing for a contending team, Meadows responded by winning 16 games for the third-place Bucs with a team-low 3.01 ERA. He had his best years with the Pirates, winning 88 games during his seven seasons in Pittsburgh. That included a stretch when few pitchers were better. “Old ‘Four Eyes’ has taken a new lease on life since his sentence to penal servitude with the Phillies has been commuted,” noted the Brooklyn Eagle.

He put his book to effective use in Pittsburgh. Since arriving in the majors, Meadows had compiled summaries and box scores of every game he pitched, noting the types and locations of pitches that batters hit successfully or couldn’t handle. “I go out and pitch with the idea that each hitter is entitled to one hit, and that I can win if I hold the team to nine hits,” Meadow said 30 years later in describing his pitching philosophy. “So, I pitch consistently to a man’s weakness, and do not switch if he hits.”

That approach made him one of the best pitchers in the league from 1925-27, when he had a 20-win season in 1926 sandwiched between two 19-game campaigns. The Pirates won the pennant in 1925, their first in 16 years, and Meadows led the team in most pitching categories. He lost 4-1 in the first game of the World Series to Walter Johnson, the Washington Senator’s legendary ace. A sore shoulder kept him from pitching again, but the Pirates erased a 3-1 game deficit to win the title in a stunner. In his next Series appearance two years later, Meadows had the misfortune of facing the New York Yankees, one of the best teams in baseball history. He lasted six innings in Game 3, yielding seven runs in an 8-1 loss. The Yankees won the next day, too, to complete the sweep.

The ailing shoulder and a recurring sinus infection forced him to retire in August 1928. Though he attempted a comeback the following season, Meadows ended his career shuffling around the low minors for a couple of years. After appearing in two games for the Bulls, he finally called it quits in 1932 in Durham where it all began almost 20 years earlier.

Meadows returned to Leesburg, Florida, where he and his wife, Catherine, or Carrie, had moved in 1923 and had raised their two children. He managed a couple of minor-league teams in the area before moving to Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1940 where he worked for the Internal Revenue Service for 11 years. He died there of a stroke in 1963.

Meadows was in the last graduating class at Horner when it was in Oxford. Most of the barracks burned down in 1914, and the school reopened in Charlotte, North Carolina. It closed six years later, and most of the site is now part of Myers Park Country Club. The main classroom building was remodeled and is now a condominium.

White was another good pitcher overshadowed by his spectacles. He won 229 games during a 10-year career, including two seasons of more than 40 wins.