Note: The is the second of four stories about my trip to the bayous of southern Louisiana. The stories are also being published at Coastal Review.

NEW ORLEANS – Our search for connections and common ground began with a tour of this storm-struck city on the Mississippi River. We didn’t set out to find the Big Easy. No double-decked tourist buses for us. No frozen daiquiris from one of the drive-throughs that seem to be everywhere. The famed French Quarter wasn’t on our itinerary. Neither were any cool jazz clubs on Bourbon Street or warm beignets at the Café Du Monde. No, ours was a melancholy excursion that took us to landmarks of our hubris, monuments to our supreme self confidence that we can control the uncontrollable.

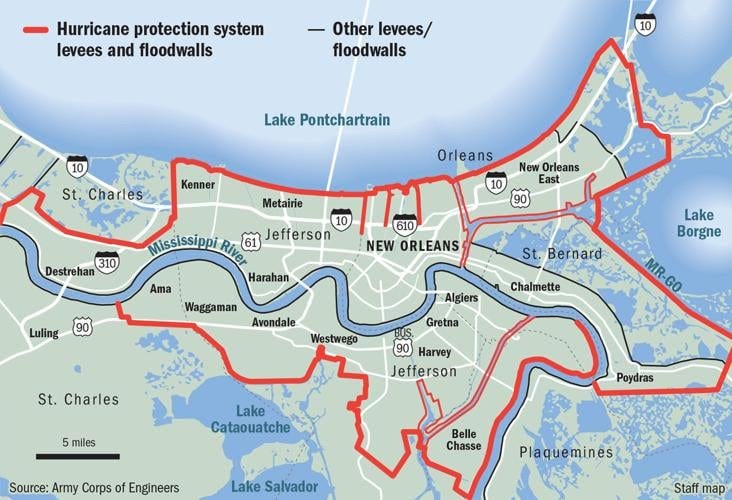

We visited the places where the levees gave way and the walls collapsed 20 years ago in August when Hurricane Katrina exposed their fragility and futility. Canals designed to drain water away from the city carried a devastating storm surge into it. One built to encourage commerce took the flood into New Orleans’ beating heart and drowned an entire parish that has yet to recover. Pumps failed, and as much as 17 feet of water ended up covering 80 percent of a city that exists mostly under sea level. Almost 1,500 people died, more than 100,000 families were left homeless, and about $200 billion worth of property was destroyed or damaged. The American Society of Civil Engineers later called it “the worst engineering catastrophe in U.S. history.”

The hurricane wasn’t the killer. We were. We thought we were gods who could contain the tempest. Rosina Philippe knows better. You’ll meet her later in our journey through the bayous of southern Louisiana. She’s an elder with the Atakapa-Ishak Nation in Plaquemines Parish, down in the far southern tip of the state. Her people have existed for centuries surrounded by water. “Water will always meander,” she told us. “It will always find you. It will go this way and that until it finds your weakness. You can never control the water. You can only try to live with it.”

It seemed like a fitting first lesson for a group of North Carolinians who spent six days in June exploring a state that a dozen hurricanes have battered since Katrina, a place where a football field of marshes disappears on average every day. As Rosina warned and Katrina attested, the calculations of engineers may not offer much protection when the storms come, and the floods threaten.

Sponsored by Duke University and led by Karen Amspacher, a Harkers Island native and the director of a cultural museum there, the group hoped to connect the people of the bayous with those living at the water’s edge in the small fishing and farming villages of low-lying eastern Carteret County, Amspacher’s beloved Down East. They face a grim future of increasing storms and flooding as the climate warms and the seas rise. Many of their homes will become uninhabitable by century’s end. Can connecting with people who have already faced those dangers raise awareness and lead to understanding and ultimately to solutions? “I don’t know if it can,” she said, “but we have to try.”

The Unexpected Flood

We drove along City Park Avenue, atop the remnants of a sand ridge that the Mississippi created eons ago, took a right on Canal Boulevard, and headed north, downhill, toward Lake Pontchartrain. In a couple of miles, we reached Lakeview, a neighborhood of handsome brick and stucco homes. We were below sea level, kept dry by the city’s extensive system of earthen walls, or levees. Look closely, advised Barry Keim, and the evidence of living below the sea is everywhere. Many of the houses’ foundations are exposed and their driveways cracked as the peat soil of the old marsh beneath them dries and compresses. Side streets are buckled, and the tops of storm drains are above the sinking pavement.

“Every house you see on both sides of the road was flooded after Katrina,” he noted. “The water here was eight to 10 feet deep, some of the worst flooding in the city.”

A thick black line around the exterior of the neighborhood Starbucks memorializes those dark times. The line is more than seven feet above the ground with one word printed above it in bold letters: “Katrina.”

“And this is where all that water came from,” Keim said standing on the seawall that borders the lake. An affable man who was the state climatologist for more than 20 years, he now directs the Environmental Health, Climate, and Sustainability Program at Louisiana State University in New Orleans. He knows the city intimately, having grown up in one of its suburbs.

Down this way, they call the oval-shaped body of water behind him a lake, though it’s technically a lagoon because it has an opening to the Gulf of Mexico at its east end. By any name, it’s big, covering more than twice the area of North Carolina’s largest city, Charlotte. Though a levee was built along the shoreline here after a 1947 hurricane flooded a portion of New Orleans, Pontchartrain was considered far less of a threat than the mighty Mississippi, which snakes along the other side of the city.

Engineers found the lake to be a convenient place to dispose of excess water as New Orleans grew from its original settlement on the high ground of a natural levee created by the river. Over time, they dug three large canals to drain the low-lying land that locals call “the Back of Town.” Katrina came along on just the right path to turn the tables, pushing its deadly surge up the canals. “Everyone expected the big flood to come from the river,” noted Amy Lesen. “No one expected the levee system here to fail as it did during Katrina.”

A professor at Antioch University and Tulane University in New Orleans, Lesen organized much of the trip to come. She has spent most of her career teaching and writing about climate change and its effects on people. A striking resume popped up on Google when I searched: BS in marine fisheries biology from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley; a long list of books and publications; an impressive array of research grants; and weighty appointments and awards. Most striking, though, is what Google only hints at. Unlike most professors, Lesen gets out of the classroom and into communities, helping the poor and disadvantaged recover from storms or prepare for them. Over the next six days, I will come to learn that she’s just a big-hearted Jewish girl from the Bronx, NY, who came to New Orleans almost 20 years ago and found her life’s work helping the marginalized water people of the bayous adjust to a rapidly changing world.

Residents of 4900 block of Warrington Drive didn’t have much time to react when Katrina arrived that morning of Aug. 29. All they could do was run for their lives. Water from the lake rushed up the London Avenue Canal, which ran through their backyards along a channel lined by concrete and sheet metal walls that had been reinforced just a decade earlier. The engineers unknowingly anchored their walls in the soft sand of an ancient barrier island, Keim said. At 9:30 a.m., a 30-foot section of the wall collapsed, releasing a geyser of sand and a torrent of water that topped 15 feet. The neighborhood disappeared. “When I drove down here, there were houses on houses, cars on top of cars,” Amy remembered. “It was complete devastation.”

We are peeking through the windows of 4918 Warrington, a solid brick house that withstood the flood. No one lives here now, and you can’t go inside. The Flooded House Museum is a stark re-creation, a haunting reminder of what the people here came back to after the flood waters receded. Dark mold covers the walls. The baby grand piano in the corner is destroyed. Yet, the books on the shelves seem undisturbed. Photo frames hang askew. Toys are tossed around the room, and a thick layer of dirt covers every piece of furniture. The wrinkled, faded front page of the city’s Times-Picayune sits atop a broken table. The newspaper was published the day before the storm. “Katrina Takes Aim,” the headline screams.

We headed back to the van. “I hate I have to take you on this tour of woe,” Amy said.

They Called It Mister Go

In the ponderous language of the bureaucracy, it’s known as the Mississippi-Gulf Outlet Canal. Locals took the acronym, MSGO, and came up with a more memorable moniker, Mister Go. It was the last and maybe most depressing stop on Amy’s tour. Of all the deadly screw-ups that led to a drowned city, Mister Go was the most predictable and most lethal.

Fittingly, then, it started to rain, though the sun was still shining, as we headed south out of town on LA 39, following the Mississippi. A huge levee obscured the river on our right, though we sometimes glimpsed the smokestacks of passing ships. “The devil is beating his wife,” Keim said from the front seat. “That’s what we say down here when it rains while the sun is shining.”

As Lucifer wailed away, St. Bernard Parish rolled by our windows. At almost 2,200 square miles, it is the state’s second-largest parish, or what we in North Carolina would call a county. Eighty-three percent of it is water, however, making it the wettest place in Louisiana, which is saying something. The passing scenery confirmed that: a thousand cuts of water coursing through an endless sea of marsh grasses, dotted by small islands of bald cypress trees. “Out here, you’re in another world,” Keim noted.

We reached our destination, Shell Beach, which has neither a beach nor any readily apparent shells. Shrimp trawlers and rusting oyster dredges were tied up along the Mister Go waterfront, confirming the community’s past prominence as a fishing port. “If you came here before Katrina, you would have seen a lot of activity,” Keim said as we got out of the van. “It was a bustling place.”

About 40 minutes from downtown New Orleans, Shell Beach is about halfway up the 76-mile channel that links the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans’ inner harbor. The city had been clamoring for years for a shortcut for commercial ships. With support from the Army Corps of Engineers, Mister Go finally got Congressional approval in 1956. The Corps started digging two years later, dredging up more earth then was moved during the building of the Panama Canal and destroying thousands of acres of wetlands in the process. The channel opened to shipping in 1965 at a cost of $92 million, or almost $900 million when adjusted for inflation.

“Scientists warned of the environmental effects, and locals worried about the flooding.” Keim explained as we walked along the deserted waterfront. “The people here didn’t want this built. They thought it would be a disaster. It turned out to be worse than they imagined.”

As soon as the channel was dug, saltwater from the Gulf swept in, drastically changing the ecosystem. The dead, sun-bleached stalks of bald cypress and live oak trees, what scientists call ghost forests, mark the salt’s line of advance. Muskrats went next, taking the parish’s thriving fur industry with them. The oysters followed along with another industry. The brackish marshes were important to wintering waterfowl, but the birds went elsewhere after the water’s salt content tripled, killing most of the marshes.

The long-term effects stretched far beyond muskrats, oysters, and ducks, however. An estimated 20,000 acres of marsh that served as a buffer against storms were swept away over the next 40 years. By the time Katrina arrived, the original 500-foot-wide channel had more than quadrupled in size in some places.

Poor people bore the brunt of what came next. Katrina’s storm surge barreled up the channel and into the connecting Industrial Canal in the heart of New Orleans. Containing walls collapsed, and the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, a predominantly Black neighborhood, was under 12 feet of water. Its residents became the storm’s human face of suffering on TVs around the world. The Lower Ninth was the last place in the city to get power restored, the last to be pumped dry. Empty lots and collapsed houses covered in vines dot it still.

In poverty-stricken St. Bernard Parish, the destruction was complete. Every inch of the parish was underwater, every building flooded. Many who fled never came back. The parish’s population is still two-thirds of what it was before the storm.

The most-maddening thing about it? All that death and all that destruction and all that despair were for nothing. Absolutely nothing. A few people probably made money on Mister Go, but the economic boom it was predicted to trigger along its length never happened. In fact, it was a bust. Before the storm, the channel cost more than $8 million to maintain each year for the two large container ships that used it on any day. In the Corps of Engineers’ long list of misjudgments, miscalculations, and disasters, the Mississippi-Gulf Outlet Canal must rank somewhere near the top.

Under extreme local pressure, the Corps shut the whole thing down after Katrina. It built a rock dam in 2009 at Mister Go’s Gulf end to close it to shipping and completed a $1.1 billion storm-surge gate across its connection to the Industrial Canal four years later. In New Orleans, it built floodgates at the mouth of the other canals.

The people of St. Bernard Parish were left to mourn, but they got busy building, too. They erected a monument along the shore in Shell Beach that lists the names of all 164 parish residents who died during the flooding: Bernhard, De la Fosse, Gallodoro, LaBlanc, Morates, Roark, Vidross…

“Those are the names of St. Bernard Parish,” Amy said.

Next: Ground zero for wetland loss in the world.

I agree with David. Excellent piece, Frank.

Powerful story, Frank, though incredibly depressing. I shudder to think how much worse it will be next time, after the ravages of our current government.